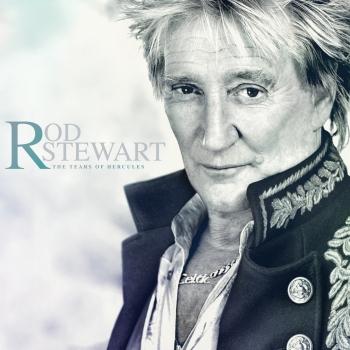

Rod Stewart

Biography Rod Stewart

Rod Stewart

“Rarely has a singer had as full and unique a talent as Rod Stewart — a writer who offered profound lyricism and fabulous self-deprecating humor, teller of tall tales and honest heartbreaker, he had an unmatched eye for the tiny details around which lives turn, shatter, and reform — and a voice to make those details indelible. His solo albums were defined by two special qualities: warmth, which was redemptive, and modesty, which was liberating. If ever any rocker chose the role of everyman and lived up to it, it was Rod Stewart.” –The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll (1980)

Typical. You wait decades for a brand new Rod Stewart song to show up, and eleven come along all at once.

Consequently this new collection from the two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee and Grammy Living Legend is a double landmark. It’s not just his first album of original material for nearly two decades; it also represents a concentrated burst of songwriting activity which is unprecedented in his five-decade career and signals the rediscovery of a gift that Stewart long since thought had deserted him.

The world knows Stewart to be a man of many facets: the fully paid-up, card-carrying rock star; the father of eight; the full-time curator of one of history’s most famous haircuts; the tireless Celtic fan; the extremely handy soccer player and provider, even now, of a devilishly in-swinging corner from the left-hand side.

The world also knows Stewart to be a songwriter – though not so much in recent years. True, in this area, Stewart has already logged more than his share of keepers – songs that will be around for as long as people listen to pop music. He is the lyricist and melodist behind such staples as ‘Tonight’s The Night’, ‘You Wear It Well’, ‘You’re In My Heart’, ‘The Killing of Georgie’ and the indelible ‘Maggie May’ – all of them miniature masterpieces of story-telling.

Yet somewhere along the way, the source of those lyrical yet direct and instantly nerve-touching narratives appeared to dry up. To the point, even, where, at the beginning of this

century, Stewart could look back at his own catalogue from a bemused and baffled distance. As he put it, ‘It was almost as if a person I didn’t know used to write those songs.’

This new album serves emphatic notice that Stewart has bumped into that person again.

The craft of songwriting lured Stewart from the beginning. As a young teenager, charged with minding his father’s London newspaper shop, Stewart would put up the ‘Closed’ sign, so as not to be disturbed, and sit out the back with an acoustic guitar, attempting to decode and master every track on the first Bob Dylan album. Yet, in the mid-Sixties, in the small, hot British blues clubs in which Stewart did his formal vocalist’s apprenticeship, first as a member of Long John Baldry’s Hoochie Coochie Men, and then in the group Steampacket, it wasn’t about writing your own songs. It was about wringing every drop of soul out of Ray Charles’s ‘The Night Time Is The Right Time’ while simultaneously wearing a sharp suit and keeping a carefully up-combed bouffant in perfect working order. The songwriting ambitions took a back seat.

Even the highly influential Jeff Beck Group, in which Stewart sang between 1967 and 1969, was largely a covers outfit. It’s a plausible argument, nevertheless, that, but for that lack of homegrown material, the Jeff Beck Group (who entirely blazed the trail for heavy rock as we know it) would have been Led Zeppelin before Led Zeppelin.

But then, perhaps, we wouldn’t have had The Faces, Stewart’s next outfit, whose liberal attitude to refreshment in the workplace and whose highly imaginative approach to the reconstruction of hotel rooms set the benchmark for rock’n’roll roistering from the 1970s onwards. It was for The Faces that Stewart, getting into his stride as a writer, came up with the eternal ‘Mandolin Wind’ and the band also saw the flowering of his collaboration with his former Jeff Beck Group cohort and lifetime pal Ronnie Wood. The pair started out unpromisingly, settling down one day in the tiny sitting room of Wood’s mum’s house in west London, armed only with a pad of blank paper and a cheap bottle of wine. The paper remained blank long after the bottle was empty. But the partnership would eventually yield, among others, ‘Stay With Me’, ‘Miss Judy’s Farm’, ‘Every Picture Tells A Story’, ‘Gasoline Alley’, ‘Cindy Incidentally’ (with Ian McLagan) and ‘Had Me A Real Good Time’ (with Ronnie Lane).

Meanwhile Stewart’s solo star had begin its vertiginous rise, substantially propelled by his own writings – a trail of international smash hits across two and half decades, from the era-defining ‘Da Ya Think I’m Sexy’, via ‘Infatuation’, ‘Baby Jane’ and ‘Hot Legs’, to the anthemic and ubiquitous ‘Forever Young’.

After which, somewhat abruptly, the muse abandoned him.

Stewart contributed the title track to the album ‘When We Were The New Boys’ in 1998, and (not for the want of trying) nothing thereafter, and was soon obliged to conclude that he was in the grip of a terminal case of writer’s block.

As he tells it, with characteristic self-effacement, “My assumption was that I was finished as a songwriter. It had always been difficult, and then, at some point in the 1990s, my confidence took a knock and it became impossible. I was thinking too hard about what people expected from me. And I was thinking about whether I felt comfortable any more, delivering whatever it was people expected from me… I was trapped down all sorts of unhelpful mental alleys, basically. And eventually I convinced myself that I had made the best of the little bit of talent for songwriting that I had been given. But now it was over – time to move on.”

Not that this left him idle, of course. There were plenty of other songs around. And Stewart always had the uncanny gift to inhabit anything he put his voice to. This, after all, is a man who can sing ‘Happy Birthday To You’ and make it sound like the number was written especially for him. He spent the first decade of the new century cutting his own path through the Great American Songbook, realizing a long-held ambition to put perhaps popular music’s least boundary-hindered voice to the classic ballads and swing tunes he heard glowing from the radiogram in his childhood London home. At an age when most of his peers were just happy to be hanging on in there, Stewart sold more records than in any other decade of his career.

And then, when least expected, the muse returned. One weekend, at home in Epping, England, Stewart’s old friend, the guitarist Jim Cregan, proposed a casual writing session. The host’s reaction wasn’t exactly eager. “To be perfectly frank,” Stewart says, “I was rather looking forward to a Sunday afternoon post-lunch snooze.”

Still, Cregan strummed and Stewart hummed and la’d. Nothing was concluded. A couple of days later, though, Cregan sent Stewart a recording of their efforts, slightly smartened up. Says Stewart, “And I played it, and the title Brighton Beach’ dropped into my head – from nowhere, as titles always used to and for no reason I could put my finger on. And right then I started writing a lyric: about taking the train down to the south coast of England as a young, beatnik kid with an acoustic guitar, and sleeping on the beach and falling in love and the sheer romance of that time.”

“And very quickly – much quicker than I was used to – I found myself with a finished song.”

This happened to be a period in which Stewart was working on what would become his internationally best-selling autobiography, ‘Rod’, published in October 2012. “Something about that process of reviewing my life for the book reconnected me,” he says. “And that was it: I was away. Suddenly ideas for lyrics were piling up in my head. Next thing I knew, I had a song called ‘It’s Over’, about divorce and separation. And now I was getting up in the middle of the night and scrambling for a pen to write things down, which has never happened to me. I finished seven or eight songs very quickly and I still wasn’t done and it became apparent that I would eventually have a whole album of material to record, which had never happened before. It’s tended to be four or five songs per album at most.”

On the new recordings, that rekindled energy is audible straight away in the mandolin-spangled, fiddle-flecked, guitar-driven burst of optimism of the album’s opener, ‘She Makes Me Happy’. And it’s there again in the skirling bagpipes and huge tune of the fist-pumping ‘Can’t Stop Me Now’, which channels memories of Stewart’s early days in search of a break before opening out into a fervent letter of gratitude to the singer’s father for his unceasing belief.

Then comes ‘It’s Over’, an unsparing vision of the mess of a disintegrated marriage, and that tale of formative days and early love which is ‘Brighton Beach’. ‘Beautiful Morning’ is a four-minute package of supercharged pop, with a Motown backbeat and a chorus which appears to be running on pure bliss. ‘Live The Live’ opens with a time-dissolving mandolin figure, and if Stewart has a manifesto to offer, you will find it just past the beautiful descending chords of that song’s bridge, in the clinching lines: ‘Live the life you love, and love the life you live.’ There’s old-school, raunchy blues-rock on ‘Finest Woman’, while the ballad ‘Time’, with its winding electric piano figure, could have come swaying off a Faces album with a pint in its hand. ‘Sexual Religion’, an irresistibly alluring song about irresistible allure, contains echoes of disco-era Stewart, but effortlessly spun forwards into the present (no leopard-print Lycra this time). Stewart’s fabled knack for an easily unfolding narrative is revived on ‘Make Love To Me Tonight’, the timeless story of a troubled working man seeking escape in his lover’s arms, and the album’s closer, ‘Pure Love’, is a father’s experience-scolded hymn of advice to his children which is so tender that it all but wraps the listener in its arms.