Olatunji

Biographie Olatunji

Babatunde Olatunji

has been hailed as the father of African drumming in the United States. For nearly fifty years he has spread a message of love with his drum. Legions of friends and students count him as a great influence in their lives -- musically as well as spiritually. Considered by many to be a "living legend," he is disarmingly friendly and open, always making time to talk with fans and admirers. Even those meeting him for the first time call him simply "Baba."

Michael Babatunde Olatunji was born in 1927 in Ajido, Nigeria, a small fishing village about forty miles from Lagos, Nigeria's capital. His childhood was filled with singing and drumming. He dreamed of becoming a diplomat for his people, and in 1950 he received a Rotary International scholarship to Morehouse College in Atlanta. When he arrived at Morehouse, Olatunji was surprised at how little his classmates knew about Africa.

"They had no concept of Africa," he recalls. "They asked all kinds of questions: 'Do lions really roam the streets? Do people sleep in trees?' They even asked me if Africans had tails! They thought Africa was like the Tarzan movies. Ignorance is bliss, but it is a dangerous bliss.

"Africa had given so much to world culture, but they didn't know it. I decided to educate my colleagues about Africa, so I would invite them to my room and we would talk about their African heritage. We'd listen to blues on the radio and I'd say, 'That's African music!' One television program we watched was I Love Lucy. Ricky Ricardo would sing, 'Baba loo, aiye!' That is a Yoruba folk song from Nigeria! It is sung by newlyweds and it says, 'Father, lord of the world, please give me a child to play with.'"

He gradually taught his fellow students some of the rhythms, songs, and dances of his native land, and in 1953 Olatunji organized his first performance of African music and dance. "That was the first African dance concert, and it was very successful," he says. "The white people came from downtown Atlanta to see it."

Olatunji graduated from Morehouse College in 1954. He received a B.A. degree in Political Science with a minor in Sociology. Still holding on to his dream of becoming a diplomat, he moved to New York City and enrolled in the Graduate School of Public Administration and International Relations at New York University. "They had no scholarships for Africans," says Olatunji, "so I worked in a ball-point pen factory. I would go to class and then I would play at The Africa Room on Lexington Avenue at night. For a time, I worked for a construction firm in Hackensack, New Jersey. I helped build the Ford Motor plant."

He organized a small drum and dance troupe and began giving school programs on African cultural heritage. In 1956, he was asked to contribute a song to the first UNICEF recording for children. Through the UNICEF recording, Olatunji was introduced to the U.N. Choir, and their director put him in touch with Radio City Music Hall arranger Raymond White. White asked Olatunji to collaborate on a performance with the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. "African Drum Fantasy" played four shows a day for seven weeks in 1958. In attendance at one of those shows was Al Han, an executive with Columbia Records. Han immediately signed Olatunji to a recording contract and produced the seminal 1959 recording Drums of Passion.

Hailed as the first album to bring African music to Western ears, Drums of Passion was a huge success, and it eventually went to number 13 on the Billboard charts. Olatunji continued his public school performances in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, and wanted to promote the album with the young students. "The people at Columbia thought the title was too risquè," Baba chuckles, "so they wouldn't help me promote it in the schools."

Drums of Passion sold millions of copies and it has never gone out of print. "I never made any money from that recording," Baba says with obvious sadness and frustration, "until I met a very fine lawyer named Bill Krasilozcky. He helped me regain ownership of the title Drums of Passion after twenty years."

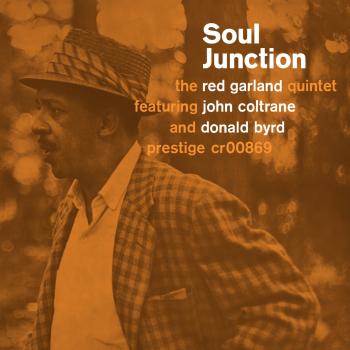

Throughout the early 1960s, Olatunji rode a wave of popularity that earned him appearances on such programs as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, The Bell Telephone Hour, and The Mike Douglas Show. He had a jazz combo at Birdland that opened for such artists as Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Quincy Jones. "Yusef Lateef was the director," he recalls, "and we played with Clark Terry, Snookie Young, Coleman Hawkins, Horace Silver, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane. We were playing 'Afro-jazz' before anybody called it that." In 1964, Olatunji organized performances at the New York World's Fair.

He used the money he made at the World's Fair to start The Olatunji Center for African Culture, which opened in Harlem in 1965. The center offered classes in African dance, music, language, folklore, and history for two dollars a class. A teacher training program was offered, and on Sundays there was the Roots of Africa concert series featuring performances by such legendary musicians as Yusef Lateef, John Coltrane, and Pete Seeger.

"John Coltrane played his last concert at my center," Olatunji remembers. "He gave us $250 every month, and the Rockefellers gave us $25,000. We applied for a Ford Foundation grant, but they said, 'We don't fund your kind of program.' It was very difficult to get support. The well-to-do black families wouldn't bring their children out. We had a children's program every Saturday, and I'd have to pick up children off the street and bring them to the center to teach them something about their cultural heritage. We were always having trouble making the rent. I had to go to court every year just to try to keep our lease."

In 1966, Columbia ended Olatunji's recording contract after releasing five albums. Asked if he was discouraged by the setback, he responds with one of his many poetic recitations, this one by British poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox. "Remember this," he says, "and I want you to write this down: 'There is no chance, no fate that can circumvent, hinder, or control the firm resolve of a determined soul. Gifts count for nothing. Will alone is great, and everything gives way before it. For there is no obstacle that can stay the mighty force of a sea-seeking river or cause the ascending orb of day to wait.'"

Having lost his recording contract, Olatunji concentrated on his teaching. From 1968 to 1982, he taught at the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in Roxbury, Mass. two days a week. Then he would fly to Ohio to teach at Kent State University, and back to New York for classes at the Olatunji Center. How did he keep such a pace? "Because I love what I do," he replies. "God had given me the opportunity to give something back to the world."

The Olatunji Center closed in 1984 due to financial difficulties. But Baba remained undeterred. "God works in mysterious ways," he says. "One door closes and another opens. You ask for direction and it is revealed to you." In November 1985, Olatunji was playing in San Francisco when Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead approached him following the concert. "You probably don't remember me," Hart said, "but you are the reason I'm playing drums today." Hart had been in the audience twenty-five years earlier when Olatunji performed at his elementary school on Long Island. "I always invited a few students to come up on stage and play with me," Olatunji says. "Mickey was one of them. I raised his hand and said, 'He's good!'"

Hart invited Olatunji to open for the Grateful Dead at an upcoming concert, and in the late 1980s Hart produced a pair of recordings for Olatunji. "Mickey Hart brought me back into circulation," says Olatunji. "That was December 31, 1985 and I will never forget it. When you give love, you get love back. Remember, it is in giving that we--what? Receive!"

Throughout his career, teaching others about African culture and drumming has been the highest priority for Olatunji. In his 1993 instructional video, Babatunde Olatunji: African Drumming (Interworld Music), he explains his famous "gun, go do, pa ta" method of drumming instruction. When asked how he came up with such a logical and systematic way of teaching, Baba naturally deflects the recognition. "I must give credit where credit is due," he says. "It was there all along! It comes from the consonants in the Yoruba language. I didn't invent the system. I just discovered it."

At 74, Baba continues to teach and perform. He plans to teach again at the Esalen Institute of holistic studies in Big Sur, Calif., where he has spent time twice a year for the past twenty-five years. His autobiography, The Beat of My Drum (Temple University Press), is slated for release in spring 2002. When he was recently hospitalized, well wishes flowed in from every corner of the globe. "Everyone was so wonderful while I was ill," he says. "Tell them Baba is back on his feet!"

For all his long-time supporters and admirers, Baba's PAS Hall of Fame nomination is a natural fit. "It couldn't have come at a better time," Olatunji remarks. "Time is the Great Resolver. You can think you aren't being recognized, but time will take care of everything.

"You know," he says, "there are two words I always ask students to define, and they both have four letters; TIME and LOVE. If you give love it will come back to you. It may not be from the source you expected, but it will come to you."

In Mickey Hart's book, Drumming at the Edge of Magic, Olatunji relates, "The Yoruba say that anyone who does something so great that he or she can never be forgotten has become an Orisha. There are several ways of celebrating these Orisha. Sometimes we make sacrifices at the shrine of the Orisha and offer them gifts. Or else a feast with drumming and dancing is planned" Sounds like a Hall of Fame banquet to me. Alafia, Baba. Asè. (www.pas.org)