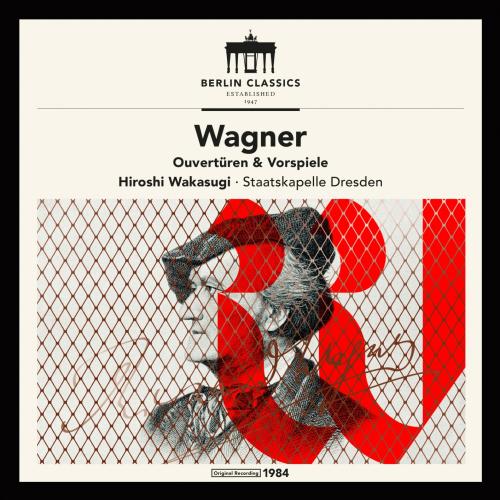

Wagner: Overtures and Preludes (Remastered) Staatskapelle Berlin

Album info

Album-Release:

1984

HRA-Release:

24.02.2017

Label: Berlin Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Staatskapelle Berlin

Composer: Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Richard Wagner (1813-1883):

- 1 Der fliegende Holländer: Overture 11:12

- 2 Tannhäuser: Overture 15:30

- 3 Rienzi: Overture 12:24

- 4 Lohengrin: Prelude I. Act 09:30

- 5 Lohengrin: Prelude III. Act 03:04

Info for Wagner: Overtures and Preludes (Remastered)

Wagner’s miraculous overtures: It is surely quite miraculous that a man whom success eluded in his early years went on to become one of the two most significant opera composers of the 19th century.

Fired with enthusiasm, the twenty-year-old Richard Wagner embarked on the composition of his opera Die Feen (the fairies), based on a play by Carlo Gozzi, and completed it as early as 1834. No-one wanted it, though. He did at least manage to premiere Das Liebesverbot (the ban on love), an excellently conceived comic opera based on Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, at the Magdeburg Municipal Theatre on March 29, 1836. However, the second performance had to be cancelled after a fistfight broke out backstage before the curtain had even risen. Incidentally, this scuffle had been triggered by a private conflict among the cast and certainly had nothing to do with the quality of the new opera! Fortunately, no major loss was incurred as only three people had turned up to watch this performance.

Anyone less enterprising might well have given up, but Wagner knew that by playing his cards right he would eventually become a reputable composer of opera.

At that time Paris was the world capital of opera and the fine arts in general. It was therefore wise of Wagner to visit the city and establish ties there. His encounter with Giacomo Meyerbeer, who dominated the operatic world of Paris, was a good start and Wagner realised that his next opera would have to be a Meyerbeer-styled grand opera. He based his libretto on a German translation, which appeared in 1836, of the novel Rienzi, the Last of the Roman Tribunes by the immensely popular and prolific English writer Baron Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

In his 1905 publication on the life of Richard Wagner, Carl Friedrich Glasenapp quotes Wagner’s assertion: “Grand opera, with all its scenic and musical splendour, its richness of effects, its large-scale musical passion, stood before me; my artistic ambition was not merely to imitate it but, with unbridled extravagance, to surpass all its previous manifestations.”

He may not have been the least bit offended when Hans von Bülow, who was later his friend for a while, described Rienzi as “the best Meyerbeer opera”.

The imitation is sublimely rendered, as this overture brilliantly demonstrates. The music critic Christine Lemke-Matwey describes it as the “only showpiece in the score that is known from radio and television broadcasts; an overwhelmingly delightful perpetuum mobile…”

What particularly stands out is the way in which major themes from the opera are skilfully elaborated so as to become imprinted in the listener’s memory. Wagner would later revert to this technique in the Tannhäuser overture.

Indeed, the opera premiered in Dresden in 1842 was a great success that enheartened the composer and earned him a permanent post as kapellmeister.

Of course, Wagner could not have foreseen that posterity would later discredit Rienzi as a work that does not belong in the Bayreuth canon. What nevertheless delighted him for many years was that his parrot, Papo, could perfectly whistle a melody from Rienzi when instructed to do so.

What the next two operas have in common is that they are available in several versions and never appeared in a “final version” as such. It was a great shame that the composer never heard Der fliegende Holländer (the flying Dutchman) performed as he had composed it, namely as a one-act opera. Even the premiere, which again took place in Dresden, featured an adapted version because it would have been technically impossible to stage the work without any breaks. In 1860, in preparation for a concert in Paris, he completely changed the ending of the opera: drawing on material from the great duet in the second act, he created a kind of apotheosis thoroughly in keeping with the stage instructions given in the libretto so that the redeemed Dutchman is seen ascending to heaven, alongside his redeeming wife. It stands to reason that the composer adopted this conciliatory ending in the overture too, which clearly anticipates the development of the plot.

In fact, the composer was very pleased with this change. He wrote the following in a letter from Paris to Mathilde Wesendonck, who was the inspirational object of his secret infatuation and wife of his patron Otto: “Now, having written Isolde’s ‘Transfiguration’, I have finally found the right ending to the Flying Dutchman overture.” This new version of the opera was soon performed in Vienna and has on this recording been adopted by Hiroshi Wakasugi, who thus follows a tradition that continued through to Otto Klemperer’s divergent production at the Kroll Opera House in Berlin during the 1920s. The unrelenting original version is being used more and more frequently nowadays.

Wagner made so many changes and additions to Tannhäuser that he may well have eventually lost track of the work’s development himself. He started to make such adjustments in Dresden as early as 1845 and was never truly satisfied with the opera’s ending. He was therefore all too pleased to be commissioned by Emperor Napoleon III at the suggestion of Princess Pauline von Metternich to prepare a thoroughly revised version of Tannhäuser for the Paris Opera. He even composed the Bacchanale, a magnificent new ballet scene that enhances the portrayal of the Venusberg, a mythical mountain realm that had appeared rather too mundane in Dresden. To accommodate this scene he even cut a third of the overture, which he had written (as is evident on this recording) in three sections. The Pilgrims’ Chorus and the evocation of Wartburg Castle are followed by a middle section that leads us into the Venusberg before returning to civilised earthly terrain.

1875 saw a further revision performed at the Vienna Court Opera under the composer’s supervision. This version was intended to combine the best of the Dresden version and the opulent Paris version. By this time, however, virtually every theatre, including Bayreuth, had become accustomed to staging its own hybrid version. The composer seems to have anticipated this lack of uniformity: Cosima Wagner noted in her diary shortly before her husband’s death: “He says he still owes the world a Tannhäuser”.

Given the orchestral line-up, the premiere of the celestially beautiful and devilishly difficult Lohengrin prelude at the National Theatre of Weimar on August 28, 1850, must have left something to be desired. However, Franz Liszt had insisted on conducting this work for Wagner, his revolutionary friend who had fled to Switzerland to evade an arrest warrant that had been issued across the German states. The composer probably did not know that eleven years were to pass before he would hear his latest work. Let us try to envision this intriguing scenario: there is Liszt standing on the podium, making a valiant attempt to give at least a halfway decent account of this extremely challenging score in difficult circumstances; and there is the composer, still living in comfort at the Zum Schwanen inn in Lucerne, following the progression of the premiere on his pocket watch with his wife by his side.

The performance had become distinctly disjointed in the second act, news that fortunately reached Wagner only much later, along with reports of “a shambles on the stage” and a “hapless vocalist in the lead role”.

On this recording, however, you can hear the prelude to the first act with its sprawling lines in the strings, which were unprecedented at the time, played by the very orchestra that Wagner likely had in mind when writing the composition. Since 1859, by which time the German Kaiser had personally lobbied to rehabilitate the composer, Lohengrin has remained an undisputed part of the Dresden Opera’s standard repertoire.

The prelude to Lohengrin is in utter contrast to the music introducing the third act, where Wagner draws on all kinds of orchestral splendour to celebrate an occasion that never comes to pass on the stage, namely the festive wedding and happy marriage of the eponymous hero to the heiress to the Brabantian throne.

Staatskapelle Dresden

Hiroshi Wakasugi, conductor

Digitally remastered

No biography found.

Booklet for Wagner: Overtures and Preludes (Remastered)