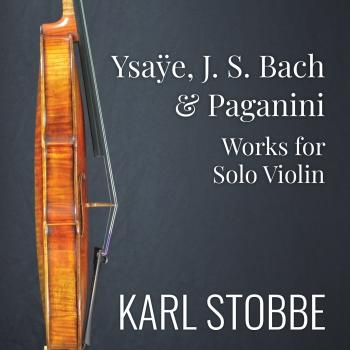

Ysaÿe, J.S. Bach & Paganini: Works for Solo Violin Karl Stobbe

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2024

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

22.03.2024

Label: Leaf Music

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Instrumental

Interpret: Karl Stobbe

Komponist: Nicolo Paganini (1782-1840), Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), Eugene Ysaye (1858-1931)

Das Album enthält Albumcover Booklet (PDF)

- Eugène Ysaÿe (1858 - 1931): Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 27 No. 4:

- 1 Ysaÿe: Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 27 No. 4: I. Allemande. Lento maestoso 05:23

- 2 Ysaÿe: Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 27 No. 4: II. Sarabande. Quasi lento 02:59

- 3 Ysaÿe: Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 27 No. 4: III. Finale. Presto ma non troppo 03:16

- Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750): Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002:

- 4 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: I. Allemanda 06:16

- 5 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: II. Double 03:48

- 6 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: III. Corrente 02:55

- 7 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: IV. Double 03:15

- 8 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: V. Sarabande 02:59

- 9 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: VI. Double 02:32

- 10 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: VII. Tempo di bourrée 03:40

- 11 Bach: Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor, BWV 1002: VIII. Double 03:29

- Niccolò Paganini (1782 - 1840): 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, MS 25:

- 12 Paganini: 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, MS 25: No. 9 in E Major "La chasse" 02:58

- 13 Paganini: 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, MS 25: No. 17 in E-Flat Major 03:41

- 14 Paganini: 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, MS 25: No. 24 in A Minor 04:39

Info zu Ysaÿe, J.S. Bach & Paganini: Works for Solo Violin

The relationship between violinist and violin—not to mention the bow—is its own kind of union. I was 20 years old when I played my first great Stradivari. It was a confusing experience for me—the sound the instrument made was beyond my ability to control, and I had never imagined such possibilities of colour and texture. In fifteen minutes with the instrument, I learned more about the violin than I had learned in my previous two years of practising! One of the pieces I played on it was the Allemanda from Bach’s B minor Partita, an experience that left a lasting impression on me. It was simultaneously humbling and exhilarating, and I had the distinct impression of being in the presence of two giants of the violin, Bach and Stradivari. I realized then that if I wanted to do them justice, there was still a lot of practising to do! Thinking on it now, it is completely inspiring to me that our artform involves the collaboration of so much genius— great violinists play music composed by great composers, on instruments made by great luthiers, creating a Single seamless listening experience.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) lived at the same time as the world’s two most illustrious violin makers, Antonio Stradivari (c. 1644–1737) and Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù,’ (1698–1744), both of whom had their workshops some 1000 km to the south, in Italy. There is no indication that Bach knew of either of them—Bach never travelled to Italy, and it is doubtful that either Stradivari or Guarneri ever left Italy. We do know, however, that Bach, as a very capable violinist himself, had an ear for quality instruments. He owned (and presumably played) an instrument by the Austrian luthier Jacob Stainer (1617–1683), who at the time was the most sought-after luthier in the world. Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly which Stainer Bach owned, or even if that instrument has survived to this day. Bach also commissioned a set of instruments for his orchestra by the important German luthier, J. C. Hoffman (1683–1750), and owned at least one of his violas da gamba.

In contrast to Bach, the great Italian virtuoso Nicolo Paganini (1782–1840) lived long after Guarneri and Stradivari, who were by then recognized as history’s most illustrious violin luthiers. Paganini is associated with at least a dozen of the finest violins from those makers, of which a 1743 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ was his preferred instrument. Its namesake, “Il Cannone,” cites Paganini’s own words when he referred to it as “my cannon violin” to describe its power and resonance. Paganini was also a close friend of one of France’s foremost luthiers, Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798–1875), who began making slight changes to the setups of the great old instruments to accommodate Paganini’s technical requirements and those of larger concert halls. Vuillaume’s changes are still used today!

In 1889, the young Belgian violinist Eugene Ysaye (1858–1931) gave a recital on “Il Cannone.” This experience generated his lifelong love of Guarneri’s work, and in 1894 he bought his main instrument, a Guarneri ‘del Gesù,’ made in 1740 and now known as the ‘Ysaye’ (which after Ysaye’s death would become the main concert instrument of Isaac Stern). Ysaye is also associated with several other luthiers and instruments, including a fine Guadagnini from 1754, several Vuillaumes, and a Nicolas Lupot from 1820 – 14 years after mine was made! With Bach, Paganini, and Ysaye, we can trace the important relationship between luthiers and players. The lore of 500 years of violin music is intertwined between performers, composers, and makers – a time travelling collaboration that is at the heart of any great performance today. And maybe this connection allows me one more little moment of reflection on violins. My violin was made in 1806 by Nicolas Lupot (1758–1824), in Paris. Lupot turns 266 in 2024. He was a great admirer of Stradivari, and one of the first to successfully study Stradivari’s work and emulate the lessons he learned in making his own instruments. When I think about Lupot and the violins that inspired him, it is amazing to me that the great violins of his day are still the same great violins of today. And as the violin world continues and evolves, Lupot’s instruments are now among some of those great violins as well. Bach, Paganini, and Ysaye each contributed to this ever-growing body of renowned instruments. Beyond the music they performed, commissioned, and composed, they also deserve accolades for their service to the luthiers, and to enriching the narratives of today’s illustrious instruments.

As the three towering figures in the history of solo violin music, pairing some music from Bach, Paganini, and Ysaye allows an opportunity to appreciate the different musical characters of the violin over time. Bach compiled the music for Sei Solo, his title for the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, BWV 1001–1006, in 1720, when formal works for solo unaccompanied instruments were quite popular. Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), Heinrich Biber (1644–1704), and Johann Paul von Westhoff (1656–1705) are among several of his contemporaries who also wrote substantial works for solo violin. We’re not entirely sure if Sei Solo was performed during Bach’s lifetime, but we do know that they were not published until 1802 and were largely ignored until the 1850s, when the great German violinist Joseph Joachim (1831–1907) began performing them.

I have always considered Bach’s B minor Partita to be the virtuosic one, not necessarily because of its difficulty (after all, they are all demanding), but rather because in playing and listening to this work one appreciates the bravura of its musical character—rather like Paganini’s Caprices discussed hereafter. All four movements are relatively short dances, each followed by a variation that lends them a slight character twist and a little added virtuosity. The Courante and its Presto variation are undoubtedly among the most dazzling of Bach’s entire output.

Bach’s death in 1750 marked both the culmination and the end of the Baroque style. The rise of the piano signalled an increase in the popularity of chamber music, and composers moved away from solo violin music, except for the studies, etudes, and caprices that were written for education and technical exercise. Practically speaking, these types of works were shorter character pieces rather than fully developed sonatas. Paganini’s 24 Caprices, op. 1 must be counted among the greatest musical and technical achievements ever contributed to this genre. Technically treacherous, but musically ingenious, they have been a source in equal parts of frustration and delight for every advanced violinist since their composition between 1802 and 1817. Whether Paganini knew of Bach’s works for solo violin remains a mystery; Bach would not be recognized as the great composer he was for 30 to 40 more years, and I doubt that an Italian violinist, even one as acclaimed as Paganini, would have had either the opportunity or the inclination to immerse himself in the complex counterpoint of a German composer whose music was probably still considered an acquired taste.

Paganini’s Caprices nos 9, 17, and 24 are my personal favourites: so difficult, but so wonderful! Each one packs so much life and joy—and each possesses its own unique character. The nobility of the hunt themes in no. 9, the swagger and playful no. 17 with its brutal, even terrifying trio, and the final Caprice, no. 24, where Paganini introduces his famous theme, used by countless other composers in their own theme-and-variations. Each has given me innumerable hours of exercise and inspiration.

One hundred years later in 1920, Ysaye knew Paganini’s Caprices and Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas intimately. It was a performance of Bach’s G minor Sonata by Joseph Szigeti (1892-1973) that inspired Ysaye to write his cycle of six Sonatas for Solo Violin, op. 27. In many ways, Ysaye combined the genius of Bach and Paganini in his Sonatas, incorporating all the flair of Paganini and the wonderful, deeply powerful counterpoint and complexity of Bach.

Whereas Ysaye’s First Sonata directly corresponds to the three solo sonatas of Bach, his Fourth Sonata seems directly inspired by Bach’s three Partitas. It employs three dance movements: an Allemanda, Sarabande, and a Presto (all worked into Bach’s Mass in B minor) and incorporates a healthy dose of exactly the type of counterpoint of which Bach would approve, including the majestic fugue at the end of the Allemanda and a magically hidden ostinato pattern that underlies the Sarabande’s structure.

This Album brings together the music of three great violinists. Although Bach’s primary instrument must be considered the organ, he was at least a highly competent violinist and at best a wonderful virtuoso in his own right. He began his professional career playing the violin and led the musicians under his direction as a violinist more than as a keyboard player. Paganini and Ysaye were both the most brilliant violinists of their generation, and their influence on the violin and western art music in general are, in my opinion, deserving of more importance than they are often credited with. But it seems important to bring one other violinist into this conversation as well: the great Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962).

When Ysaye wrote his six sonatas, he dedicated each one to a violinist he admired. The Fourth Sonata is dedicated Kreisler. In fact, the last movement almost directly quotes from Kreisler’s famous Praeludium and Allegro of 1905. Ysaye captures the elegant and refined spirit of his younger colleague with uncanny awareness, making it more than just a dedication, but a tribute to a musical soul he seemingly understood completely. Kreisler was known to have a special affinity for Bach’s B minor Partita, and he made his own arrangement of Paganini’s 24 Caprices for piano and violin. I evoke my earlier comments here about violins: Kreisler also played several violins, including a 1733 Stradivari and a 1733 Guarneri that both bear his name, as well as a 1740 Guarneri, also owned by Paganini. This is just another remarkable link in the history of violins—many violinists who might have lived centuries apart are still connected through the violins they played. The violin world might be 500 years old, but from this perspective, it still seems small! When I thought about what to pair with the B minor Partita, it was Kreisler’s connection to all these pieces that convinced me this was the right repertoire for this Album.

Karl Stobbe, violin

Karl Stobbe

is recognized as one of Canada’s most accomplished violinists, known for his dedication to excellence on the violin and classical music in all its forms. As a concertmaster, soloist, and chamber musician, Karl has been an audience favorite in small settings and large venues. His diverse career has included performances of all six Ysaÿe Sonatas for Solo Violin, all 16 Beethoven String Quartets, and all 10 Mahler Symphonies. He feels equally comfortable directing an orchestra without conductor, performing as a soloist with orchestra, playing chamber music, or giving an unaccompanied recital. Noted for his generous, rich sound and long, poignant phrasing, he is described by the San Francisco Classical Voice as “an artist with soulful musicianship,” and by London’s Sunday Times as “a master soloist, recalling the golden age of violin playing... producing a breathtaking range of tone colours.”

Karl has performed in many of North America’s most famous concert halls, including Carnegie Hall, Jordan Hall, the National Arts Centre, Roy Thompson Hall, Segerstrom Hall, and the Orpheum Theatre. As a chamber musician, soloist, and orchestra director, he has shared the stage with many of the most important and eclectic violinists of our day, from James Ehnes to Mark O’Connor. Avie Records’ recording of Karl performing Ysaÿe’s Solo Violin Sonatas received worldwide attention, including Gramophone magazine which hailed it as “full of spirit and energy... exciting, fearless...” It was nominated for a 2015 JUNO Award for Best Classical Album. The year 2015 also saw the release of a live recording of Karl, joined by Jonathan Crow and the National Arts Centre Orchestra, for the title track of “Cobalt,” a CD of the music of Jocelyn Morlock. Karl frequently performs and records new music and has been involved in numerous commissions and world premieres.

Always looking to expand the concert stage, Karl has recently created a series of online concerts for digital concert platforms. Distinguished by his life-long love of the music for solo violin, this series features video recordings of all the unaccompanied violin repertoire of J.S. Bach. In honour of the 300 th anniversary of Bach’s famous Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, it also explores Bach’s influence through video performances of other solo violin repertoire of music by Bartok, Ysaye, Prokofiev, Biber, and others.

A lover of all things violin, Karl completed a minor in Violin Repair and Construction while completing his Master’s of Music at Indiana University. His passion for the construction and mechanics of the violin is an important part of his professional musical life and continues to influence his performances and teaching. Karl never misses an opportunity to see and play exceptional violins and bows. He has given multiple presentations on the history of the violin family, violin building and repair, and organized exhibits and lecture recitals on rare, fine instruments at various concert halls, art galleries, universities, and conservatories. Karl plays on an exceptional and rare violin by Nicolas Lupot, in Paris, 1806.

Booklet für Ysaÿe, J.S. Bach & Paganini: Works for Solo Violin