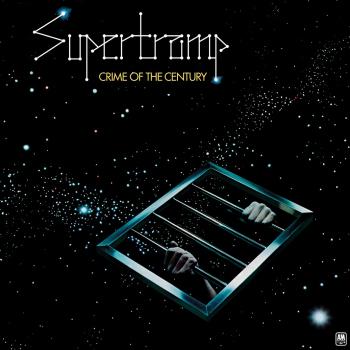

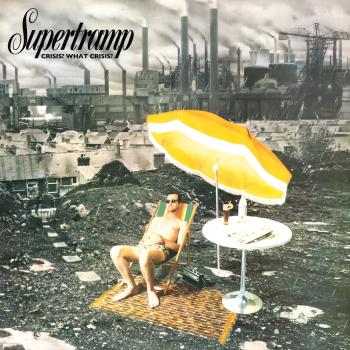

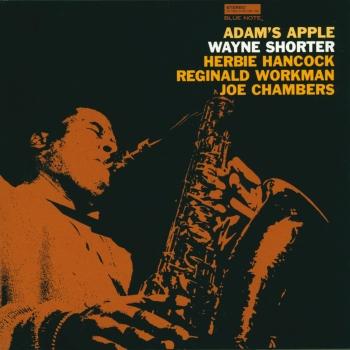

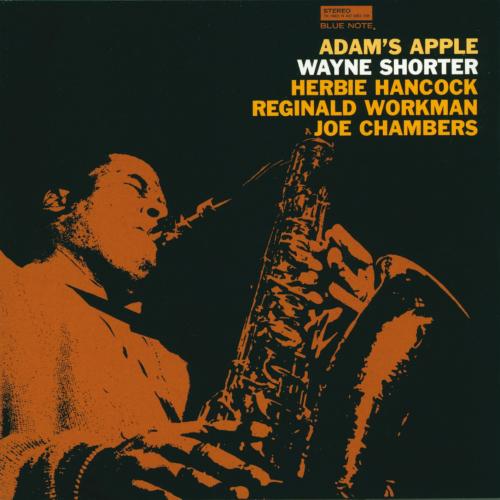

Adam's Apple Wayne Shorter

Album info

Album-Release:

1966

HRA-Release:

18.01.2014

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Adam's Apple 06:51

- 2 502 Blues (Drinkin' And Drivin') 06:35

- 3 El Gaucho 06:32

- 4 Footprints 07:30

- 5 Teru 06:14

- 6 Chief Crazy Horse 07:37

Info for Adam's Apple

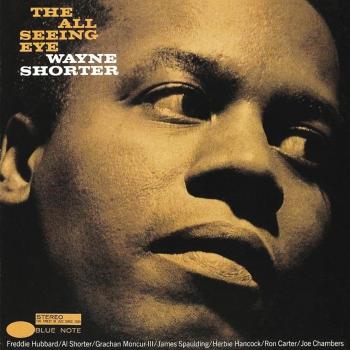

It is unclear whether it was Wayne Shorter’s initial intention to do anything particularly ambitious during the two visits to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in February 1966 that produced Adam’s Apple. Certainly, neither the repertoire—five recently composed Shorter tunes in AABA format and “502 Blues,” by pianist Jimmy Rowles, a hard drinker, as Shorter was at the time (the subtitle denotes the police code for drinking and driving)—nor the treatments contain the radical originality of the five pieces comprising The All-Seeing Eye, recorded four months earlier. Nor is there is a hint of the form-bending improvisational procedures that he, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams were deploying on a nightly basis in the Miles Davis Quintet, for which he’d already composed several consequential pieces—among them “Footprints”—since joining the group in September 1964. Nor does Adam’s Apple contain the vaguely surreal, dreamy, cinematic, parallel universe quality of Etcetera (which would not be heard until 1980) from the previous June.

Rather, Adam’s Apple coheres more closely to such prior vehicles for Shorter’s individualistic tenor saxophone voice as Second Genesis, a VeeJay blues-and-standards swinger from 1960, and JuJu, a kinetic, effervescent session done for Blue Note in August 1964 positioned halfway between the John Coltrane Quartet (the rhythm section are Coltraneans McCoy Tyner, Reggie Workman, and Elvin Jones) and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, in which Shorter would serve as Musical Director for another month. On Adam’s Apple, even at higher velocities, the ambiance is reflective, with time feels ranging from swing to slow drag to straight-eighth funk to bossa nova. Shorter’s tone is sumptuous in all tempos and registers; Hancock’s voicings and solos epitomize taste placed at the service of imagination; Workman executes the function to perfection and solos with flair; Chambers plays with the blend of surge, touch, and orchestrative nuance that guaranteed that any mid-‘60s Blue Note recording he performed on would be synonymous with excellence.

All of Shorter’s songs on Adam’s Apple have legs, not least his universally covered 6/8 minor blues “Footprints,” here addressed in an in-the-pocket, a la Coltrane manner eight months before Miles Davis stamped it forever with a complex, elegant, tension-and-release treatment that would appear on the 1967 release Miles Smiles. It remains in the book of Shorter’s current quartet with Danilo Perez, John Patitucci, and Brian Blade, as does the Coltrane homage “Chief Crazy Horse,” highlighted by the leader’s soaring, under-control solo flight. Percolating Samba rhythms propel the flow of “El Gaucho,” a wide-open-spaces melody on which Shorter foreshadows his incipient obsession with the sounds of Brazil. On the more introspective side, “Teru” is an exquisite ballad—recently covered by David Binney and Bob Belden—with an Ellington-Strayhorn quality enhanced by Shorter’s vibrato-less reading, which imparts the quality of art song, or an aria.

“I heard Adam’s Apple when I was 14. All the tunes are amazing. Wayne is completely grounded in the era before him, but something about his approach and writing and interaction with Herbie Hancock clearly felt like it was pointing towards the future, a different aesthetic from before. He didn’t seem to have an agenda to be radical, to be self-consciously, jarringly avant-garde, but rather to make something beautiful and true to what he wanted to express. That stance attracted me, that you don’t have to be jarring to be on the forefront of something new—it can be pretty, too.” (Chris Potter)

Wayne Shorter, tenor saxophone

Herbie Hancock, piano

Joe Chambers, drums

Recorded at Van Gelder Studios, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. February 3, 1966 and February 24, 1966.

Engineered by Rudy Van Gelder.

Produced by Alfred Lion.

Digitally remastered.

Wayne Shorter

Though some will argue about whether Wayne Shorter's primary impact on jazz has been as a composer or as a saxophonist, hardly anyone will dispute his overall importance as one of jazz's leading figures over a long span of time. Though indebted to a great extent to John Coltrane, with whom he practiced in the mid-'50s while still an undergraduate, Shorter eventually developed his own more succinct manner on tenor sax, retaining the tough tone quality and intensity and, in later years, adding an element of funk. On soprano, Shorter is almost another player entirely, his lovely tone shining like a light beam, his sensibilities attuned more to lyrical thoughts, his choice of notes becoming more spare as his career unfolded. Shorter's influence as a player, stemming mainly from his achievements in the 1960s and '70s, has been tremendous upon the neo-bop brigade who emerged in the early '80s, most notably Branford Marsalis. As a composer, he is best known for carefully conceived, complex, long-limbed, endlessly winding tunes, many of which have become jazz standards yet have spawned few imitators.

Shorter started on the clarinet at 16 but switched to tenor sax before entering New York University in 1952. After graduating with a BME in 1956, he played with Horace Silver for a short time until he was drafted into the Army for two years. Once out of the service, he joined Maynard Ferguson's band, meeting Ferguson's pianist Joe Zawinul in the process. The following year (1959), Shorter joined Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, where he remained until 1963, eventually becoming the band's music director. During the Blakey period, Shorter also made his debut on records as a leader, cutting several albums for Chicago's Vee-Jay label. After a few prior attempts to hire him away from Blakey, Miles Davis finally convinced Shorter to join his Quintet in September 1964, thus completing the lineup of a group whose biggest impact would leap-frog a generation into the '80s.

Staying with Miles until 1970, Shorter became at times the band's most prolific composer, contributing tunes like 'E.S.P.,' 'Pinocchio,' 'Nefertiti,' 'Sanctuary,' 'Footprints,' 'Fall' and the signature description of Miles, 'Prince of Darkness.' While playing through Miles' transition from loose post-bop acoustic jazz into electronic jazz-rock, Shorter also took up the soprano in late 1968, an instrument which turned out to be more suited to riding above the new electronic timbres than the tenor. As a prolific solo artist for Blue Note during this period, Shorter expanded his palette from hard bop almost into the atonal avant-garde, with fascinating excursions into jazz/rock territory toward the turn of the decade.

In November 1970, Shorter teamed up with old cohort Joe Zawinul and Miroslav Vitous to form Weather Report, where after a fierce start, Shorter's playing grew mellower, pithier, more consciously melodic, and gradually more subservient to Zawinul's concepts. By now, he was playing mostly on soprano, though the tenor would re-emerge more toward the end of WR's run. Shorter's solo ambitions were mostly on hold during the WR days, resulting in but one atypical solo album, Native Dancer, an attractive side trip into Brazilian-American tropicalismo in tandem with Milton Nascimento. Shorter also revisited the past in the late '70s by touring with Freddie Hubbard and ex-Miles sidemen Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams as V.S.O.P.

Shorter finally left Weather Report in 1985, but promptly went into a creative slump. Still committed to electronics and fusion, his recorded compositions from this point became more predictable and labored, saddled with leaden rhythm sections and overly complicated arrangements. After three routine Columbia albums during 1986-1988, and a tour with Santana, he lapsed into silence, finally emerging in 1992 with Wallace Roney and the V.S.O.P. rhythm section in the 'A Tribute to Miles' band. In 1994, now on Verve, Shorter released High Life, a somewhat more engaging collaboration with keyboardist Rachel Z.

In concert, he has fielded an erratic series of bands, which could be incoherent one year (1995), and lean and fit the next (1996). He guested on the Rolling Stones' Bridges to Babylon in 1997, and on Herbie Hancock's Gershwin's World in 1998. In 2001, he was back with Hancock for Future 2 Future and on Marcus Miller's M². Footprints Live! was released in 2002 under his own name, followed by Alegría in 2003 and Beyond the Sound Barrier in 2005. Given his long track record, Shorter's every record and appearance are still eagerly awaited by fans in the hope that he will thrill them again. Blue Note Records released Blue Note's Great Sessions: Wayne Shorter in 2006. (Richard S. Ginell). Source: Blue Note Records.

This album contains no booklet.