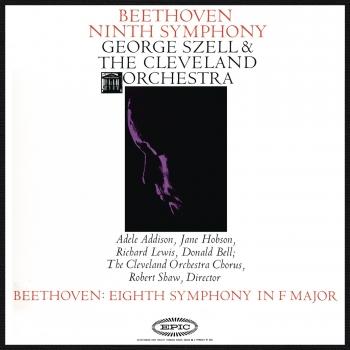

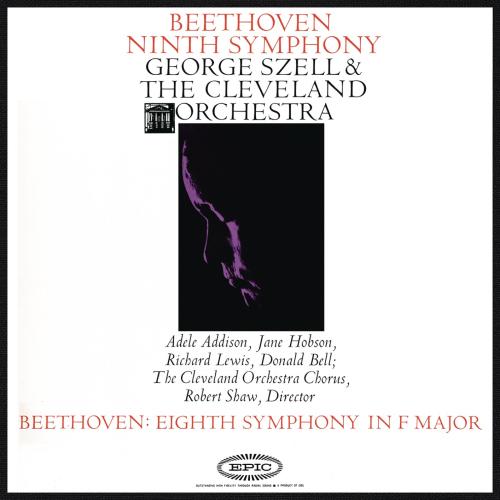

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 8 & 9 (2018 Remastered Version) Cleveland Orchestra & George Szell

Album info

Album-Release:

2018

HRA-Release:

18.08.2023

Label: Sony Classical

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Cleveland Orchestra & George Szell

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827): Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 "Choral":

- 1 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 "Choral": I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (2018 Remastered Version) 15:33

- 2 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 "Choral": II. Molto vivace (2018 Remastered Version) 11:23

- 3 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 "Choral": III. Adagio molto e cantabile - Andante moderato (2018 Remastered Version) 15:20

- 4 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 "Choral": IV. Finale (Final Chorus on Schiller's "Ode to Joy") (2018 Remastered Version) 24:02

- Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93:

- 5 Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93: I. Allegro vivace e con brio (2018 Remastered Version) 09:43

- 6 Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93: II. Allegretto scherzando (2018 Remastered Version) 03:47

- 7 Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93: III. Tempo di Menuetto (2018 Remastered Version) 05:26

- 8 Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93: IV. Allegro vivace (2018 Remastered Version) 07:50

Info for Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 8 & 9 (2018 Remastered Version)

George Szell was born in Hungary. He grew up in Vienna, where he studied composition with Eusebius Mandyczewski and piano with Richard Robert. He also studied piano in Prague with J. B. Foerster. Even as a child he played the piano and composed with passion. At the age of 17, he was already conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra with a program that included one of his own compositions.

As a conductor, he held significant posts from first conductor of the Berlin State Opera to general music director of the German Opera and the Philharmonic in Prague.

He also conducted the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow, while maintaining a steady collaboration with the Residentie Orkest in The Hague. Finally, he conducted the Metropolitan Opera during World War II. After Szell finally accepted American citizenship in 1946, he became music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. He conducted this orchestra for more than 20 years. For the last two years of his life, he also served as music advisor and principal guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

Symphony #8: For years, critics had flogged Beethoven's symphonies as grossly out-of-scale, misshapen grotesqueries. With the Eighth, the composer returned to the proportions, at any rate, of the Haydn symphony. Critics then landed on him for writing something so trivial. He couldn't win or write in any vein without somebody telling him he was doing it wrong. This symphony gets characterized – wrongly, I believe – as "merry." Although it does have its clever and droll side, I find far more prominent, in the first movement especially, a cosmic, elemental quality. Beethoven writes with a concentration which increases the power of his ideas. I know of no composer better able to evoke immensities of scale in so few notes. Wagner, Bruckner, and Mahler are downright windbags in comparison. Mendelssohn is often as economical, but not as powerful. Szell takes the first movement as if it were Eroica, Part II, with that same buoyant, rolling gait, almost like a Zeppelin taking off. The second movement, "Allegretto scherzando," makes jokes about scale. A very delicate idea begins in the high strings and winds. Beethoven then turns it over to the heavier cellos and basses – Bottom among the fairies, if you like. He even turns this around by giving weightier ideas to the lighter strings – the sprites mocking Bottom. I doubt whether Haydn would have recognized the third movement by Beethoven's title of minuet. It stands a long way from the court dance, or any dance, for that matter. Some conductors inflate it like Rudyard Kipling's frog. No worries about Szell. He reserves his fire for the trio, a gust of full-blown Romanticism before others jumped on the wagon, beautifully expansive. First horn Myron Bloom sends out lines that stretch forever. For the finale, Szell gives us what Tovey described as "the laughter of the blessed gods." Beethoven essentially takes the tropes of martial music and turns them into something supremely comic, an awe-inspiring blend of lightness and muscle. A high point of the set.

Symphony #9: As with the Eroica, I can find fault with every recording of this I've heard, on the grounds of interpretation, playing, or sound quality. A great many Ninths act as if they can't wait to get to the choral finale, the other movements merely necessary stations on the way to the Ascension. To me, the hardest movements are the first and the slow third. Apparently, conductors can easily lose their way in the first and run out of gas before the end of the third.

As fine as it is, Szell's Ninth just misses, I think, something extraordinary. It comes down to the first movement. At the beginning, one gets a sense of tremendous expectation, like holding your breath as you wait for catastrophe. One can find much to admire here – from the crisp rhythms rapped out by the brass and strings, the perfect ensemble, the contrapuntal clarity, and Szell's ability to sing the lyrical parts of the movement without getting soppy. However, Szell's usual classical restraint seems to me a mistake here. Beethoven has left the black-and-white Kansas of classicism behind. He's definitely striving for something new, even new to himself – wilder, more turbulent, less inhibited. Szell's account misses that extra ounce of oomph in the climaxes. It's a lost opportunity, because his readings of the other movements surpass all but a few and indeed emphasize Beethoven's new turmoil, without losing proportion and control. Some conductors give you excitement by pushing past the breaking point. Normally, Szell increases the vitality of his readings by exercising greater control. He twists up to and never past the breaking point. I prefer his way. In this case, however, control becomes caution. We miss the daring of the orchestra dancing on the edge.

The Cleveland Orchestra

George Szell, conductor

Digitally remastered

Please Note: We offer this album in its native sampling rate of 96 kHz, 24-bit. The provided 192 kHz version was up-sampled and offers no audible value!

George Szell

Szell’s music-loving family moved to Vienna in 1900, where four years later, already showing signs of exceptional musical gifts, he became a piano student of Richard Robert. In addition he studied composition and music theory with Foerster, Mandyczewski and Reger. Szell made his debut as both a pianist and a composer with the Vienna Tonkünstler Orchestra in 1908, and then, hailed as ‘the new Mozart’, he undertook a tour of Europe during the 1909–1910 concert season which included a visit to London. He signed a ten-year contract with the Viennese music publishing company Universal Edition in 1912, and in the same year gave the first performance of his Piano Quartet Op. 1, with the Rosé Quartet. His (unplanned) debut as a conductor came during the following year while staying with his family at the resort of Bad Kissingen, when the regular conductor of the spa’s summer concerts injured his arm.

This was followed in 1914 by a successful debut with the Blüthner Orchestra in Berlin as composer, conductor, and pianist. Between 1915 and 1917 Szell worked as a répétiteur at the Court Opera in Berlin, where he came into close contact with Richard Strauss, who recommended him to Pfitzner as the replacement for Klemperer as first conductor at Strasbourg (1917–1918). From 1919 to 1921 he was an assistant conductor at the German Opera House in Prague, before moving successively to conducting positions at Darmstadt (1921–1922) and Düsseldorf (1922–1924). Szell was then appointed first conductor at the Berlin State Opera under Erich Kleiber, remaining there for five years before returning to Prague to take up the position of chief conductor at the German Opera House, conducting in addition the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. He made his American debut with the St Louis Symphony Orchestra in 1930, and he also appeared as a guest conductor with the Courtauld-Sargent concerts in London and with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam.

As the political situation in Central Europe deteriorated, Szell left Prague in 1937 to become conductor of the Scottish Orchestra for two seasons while also serving as guest conductor of The Hague Residentie Orchestra. During the summer months of 1938 and 1939, he also conducted the orchestras of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation before moving to the USA where he settled permanently, arriving in New York during August 1939 by way of Vancouver. During the following year he taught at the Mannes School and the New School for Social Research before resuming his conducting career during the 1940–1941 season with concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, with the Detroit and NBC Symphony Orchestras and at the Ravinia and Robin Hood Dell Festivals. He made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, in 1942 conducting Richard Strauss’s Salome, and he returned regularly as a guest conductor until 1954, while also appearing with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic and Philadelphia Orchestras.

During the 1944–1945 and 1945–1946 seasons Szell appeared as guest conductor with the Cleveland Orchestra before being invited to become its chief conductor from the 1946–1947 season, having taken American citizenship in 1946. He remained at the head of the Cleveland Orchestra for the rest of his life, transforming it into one of the finest symphony orchestras in the world. During the summer months he would return regularly to Europe to appear with major orchestras at festivals such as those in Holland, Lucerne, and Salzburg, and to record. He died in 1970 following an exhausting tour of the American West Coast and the Far East with the Cleveland Orchestra.

Szell was a ruthless orchestral disciplinarian, the results of which may be heard in his numerous recordings with the Cleveland Orchestra, virtually all of which were made for the American Columbia label. His desire for musical and technical perfection was so great that occasionally he would over-rehearse a work, and members of the Cleveland Orchestra would claim that the best performances which it gave were often those at the start of a rehearsal period. Szell was equally adept at interpreting a very wide repertoire. His Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven were tightly controlled but vigorous; his Mozart concerto recordings with his close friend and fellow Richard Robert pupil, Rudolf Serkin, remain outstanding. In the repertoire of the nineteenth century Szell was pre-eminent: powerful in Wagner and highly empathetic in Brahms, Schumann and Dvořák, to name just three composers from this period. He was in addition a staunch advocate of contemporary composers, leading the first performances at Cleveland and Salzburg of works by composers such as Dutilleux, Egk, Hindemith, Liebermann and Walton. Among the relatively few live recordings of Szell in concert that have been published, those from the Cleveland Orchestra’s legendary European tour of 1967, when it visited the Edinburgh, Lucerne and Salzburg Festivals, are especially outstanding, conveying unparalleled virtuosity, control and musical insight. Several of these performances have been published on the Swiss labels Ermitage and Aura.

This album contains no booklet.