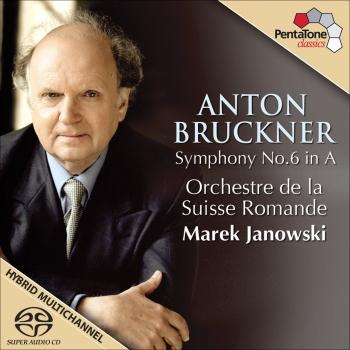

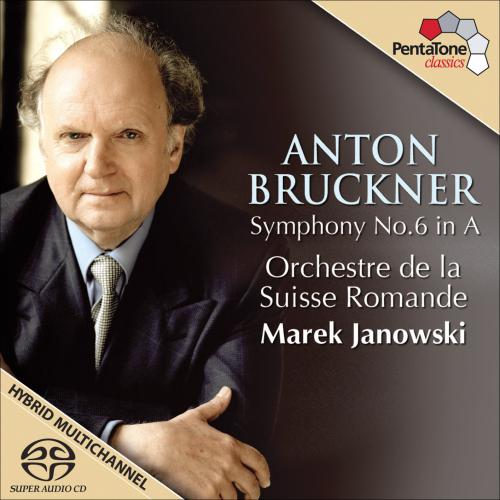

Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A (Nowak Edition) Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Album info

Album-Release:

2009

HRA-Release:

18.07.2013

Label: PentaTone

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Composer: Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A major, WAB 106

- 1 I. Maestoso 18:03

- 2 II. Adagio, sehr feierlich 17:45

- 3 III. Scherzo Nicht schnell - Trio Langsam 08:55

- 4 V. Finale Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell 12:55

Info for Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A (Nowak Edition)

As this symphony is the first not to be subjected to extensive revision by the composer, an interested person scrutinising or listening to Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 6 in A major is not forced to deal with the complex aspect of the various versions available. Consequently, for a change, it is available in just the one version. Thus one might conclude that this positive fact facilitates the access to the Symphony No. 6. After all, in the past, musicologists, conductors and audiences alike have struggled – and still struggle to this day – with the tangled web of versions in numerous other symphonies written by Bruckner. Nevertheless, we are still a long way from giving the work a straightforward and unconditional reception – indeed, the Symphony No. 6 receives rather shabby treatment in the concert hall and in Bruckner discographies, despite the fact that it is the shortest symphony ever written by Bruckner. Then why is the Sixth allotted the role of a “hanger-on”? Perhaps because it does not tie in with our image of Bruckner – perhaps due to its novel structure, its patently obvious complex of themes, or the massive upgrading of its slow movement?

Bruckner wrote his Symphony No. 6 over a period of the two years between September 1879 (directly following his String Quintet) and September 1881. To be precise – as specialist literature is always eager to emphasize – in a “creative period” that encompassed the work on his Symphonies Nos. 6 – 8, as well as his Te Deum. On February 11, 1883 the two inner movements were performed in Vienna: however, they were not given a hugely successful reception. The première of the entire work, which was conducted by Gustav Mahler, did not in fact take place until after Bruckner had died; to be sure, in an abbreviated and revised version. Numerous adaptations also crept into the first edition, which were not eliminated until the Robert Haas edition issued in 1935 (the year in which the première of the original version finally took place!). Bruckner himself never heard his Sixth Symphony performed in public; only within the context of a rehearsal in which the piece was given a play-through. However, he was apparently so satisfied with the results of his work that he decided not to carry out any revisions. This attitude was all the more remarkable, considering how rarely it was adopted by the perfectionist Bruckner. The composer described his Symphony No.6 as his “boldest” – and indeed, it sounds modern, innovatory, well-nigh avant-garde.

Following the brilliant core idea of his Symphony No. 5, in which everything is geared towards the cyclical intensification in the final movement of the theme from the first movement, Bruckner radically shifts the structural emphasis in his sixth. As if he had already solved the problem of the finale in his previous symphony, here the first movement and especially the Adagio are placed in the centre of the action.

The first movement begins restlessly, with the violins playing triplets in C-sharp minor, the upper mediant of the main key of A major, before the strikingly catchy main theme, with its descending fifth interval and Phrygian twists, claims centre stage. It seems as if a “couple” consisting of two structural opposites – unrest and restrained power – is establishing itself from the beginning onwards, traversing the entire work in similar dialectical forms. For example, various motifs suggest to the listener an inner peace; however, these are rapidly undermined or eroded by other musical parameters. This leads to tension and irritation. The rhythm typical of Bruckner – that combination of two notes against three – determines the entire first movement, including the lyrical second theme and the energetically syncopated third theme. In the development, Bruckner is clearly restraining himself, occupying himself exclusively with the first theme, and achieving by means of this concentration an enormous compression in the progression of the music. He does not allow matters to get out of hand, as usual; no, he works tersely and concisely – and succeeds in misleading the listener. Thus, on two occasions, the first theme breaks through: the first time appearing as a kind of “fake recapitulation”, whose task it is to provide the second break-through – which is the true one – with the necessary consequence to which the climax of the movement (and of the entire work!) is entitled.

The heart of the Symphony No. 6 is the tremendous Adagio, which also provides a counterweight to the first movement and undergoes a massive intensification of expression. The movement commences with a violin cantilena in double counterpoint and an accompanying plaintive oboe motif; the second theme in the cellos is led to a hymnic intensification, before a third theme makes its entrance, like a funeral march in the minor key. Instead of an actual development, the three themes are varied by adding semiquaver figurations and, at the same time, subjected to intricate intensification.

Perhaps the Scherzo is the greatest prophet of music yet to come. In complete contrast to his usually rather robust dance movements, with typically Austrian characteristics and a clearly down-to-earth tendency, in the Scherzo of the Symphony No. 6 Bruckner allows almost “Mahlerian” tones to ring out. Light melodic lines appear to hover overhead, drifting weightlessly in the air; a true breath of chamber music until, as a total surprise, the main theme of the otherwise so totally different Symphony No. 5 is quoted in the Trio. Not until the Scherzo of the Symphony No. 9 did Bruckner recreate such an unreal atmosphere.

The Finale derives its entire thematic material from the first movement – even the Phrygian touch at the outset reminds one of the beginning of the symphony. May one thus deduce from this observation that Bruckner was able to achieve cyclical unity only at the cost of an independent thematic structure in the Finale? Absolutely not: after all, it is definitely not the task of the main theme from the first movement to be employed, as it were – and as was the case in the Symphony No. 5 – in order to increase the mystic effect. On the contrary: at the end of the Finale-Coda, the main theme refers to the actual climax of the work that, as described above, already takes place at the beginning of the recapitulation of the first movement. Although admittedly the Finale represents the conclusion of the work, it does not necessarily add anything to the symphony as far as thematic material and content are concerned.

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Marek Janowski, conductor

No biography found.

Booklet for Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A (Nowak Edition)