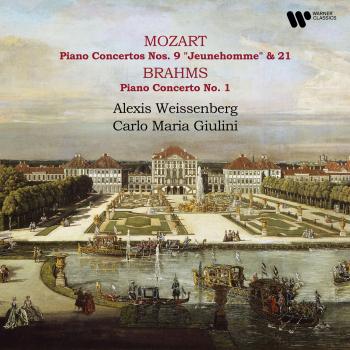

Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 9 "Jeunehomme" & 21 - Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1 (Remastered) Alexis Weissenberg & Carlo Maria Giulini

Album info

Album-Release:

1979

HRA-Release:

29.08.2025

Label: Warner Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Concertos

Artist: Alexis Weissenberg & Carlo Maria Giulini

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791): Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-Flat Major, K. 271 "Jeunehomme":

- 1 Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-Flat Major, K. 271 "Jeunehomme": I. Allegro 10:28

- 2 Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-Flat Major, K. 271 "Jeunehomme": II. Andantino 14:13

- 3 Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-Flat Major, K. 271 "Jeunehomme": III. Rondeau. Presto 10:10

- 4 Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467: I. Allegro maestoso (Cadenza by Weissenberg) 13:49

- 5 Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467: II. Andante 08:12

- 6 Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467: III. Allegro vivace assai (Cadenza by Weissenberg) 06:36

- Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897): Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 15:

- 7 Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 15: I. Maestoso 23:39

- 8 Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 15: II. Adagio 14:27

- 9 Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 15: III. Rondo. Allegro non troppo 12:12

Info for Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 9 "Jeunehomme" & 21 - Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1 (Remastered)

This 1979 recording is pure class — clear, emotional, and full of life. The “Elvira Madigan” concerto? Yeah, it’s here and sounds amazing. Perfect for chill moments or when you need focus. Weissenberg’s touch? Crisp. Giulini’s direction? Smooth. No overblown drama, just honest music done right.

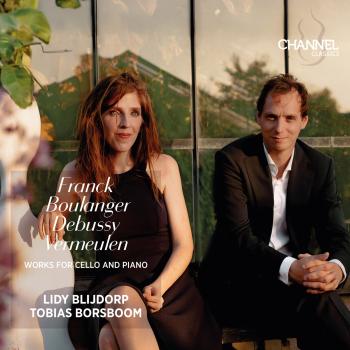

Mozart’s Piano Concertos No. 9 and No. 21, played by Alexis Weissenberg with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini. Dated 1979, but I found a reissue, probably early 80s. Angel Records, tan label with a little angel sitting on a disc. Kinda cute. Felt like I was unearthing treasure, not just some old classical record. First thing—Weissenberg. Dude’s got touch. Like, fingers made of moonlight or something. In K.271 (the E-flat one), that first movement—Allegro maestoso—it’s bold, but he doesn’t smash it. He dances. There’s weight, sure, but also this playful flick at the end of phrases. Like he’s winking at Mozart. And the orchestra? Tight. Giulini doesn’t over-cook it. Lets the piano breathe. No drama for drama’s sake. Good. Then the K.467—the “Elvira Madigan” one. Everyone knows that second movement, right? The Andantino. Slow, sad, beautiful. Weissenberg plays it like he’s confessing something. Barely touching the keys. Haunting. I played it once and my roommate walked in like, “Who died?” That’s how heavy it feels. In a good way. Like, emotionally real. But not everything’s perfect. The balance sometimes feels… off. Like the piano’s a bit too forward in the mix. You lose some of the orchestral texture. Especially in the Rondeau of K.271. It’s bouncy, but the strings get a little buried. Feels like you’re in a room with a great pianist and a slightly muffled band behind a curtain. And okay—maybe it’s the vinyl, maybe it’s the mastering—but there’s a slight hiss. Not annoying, just there. Like the ghosts of 1979 are whispering in the background. Could be charm. Could be noise. Depends on your mood. I like that Weissenberg wrote his own cadenzas for K.271. Shows guts. They’re not flashy, just smart. Fit the piece. Respectful but not boring. Mozart would probably nod, maybe smirk. Cover’s got a painting of Nymphenburg Palace. Fancy. Feels appropriate. Like you’re being invited into someone’s elegant, slightly dusty world. Funny thing? I’ve listened to this while cooking, cleaning, even arguing with my landlord over text. And every time the Andantino kicks in, I stop. Just freeze. Doesn’t matter what I’m doing. That melody cuts through everything. Makes you remember you’re human. Would I recommend it? Yeah. Not because it’s the “best” version out there. There’s faster pianists, flashier ones. But this one? It feels honest. Like they’re not trying to impress. Just play. And sometimes, that’s more than enough. Also—kinda weird thought—what if Mozart actually liked this? Like, what if he time-traveled, sat in the back of the hall, and went, “Huh. Not bad, Weissenberg. Not bad at all.” Would’ve been a good day for him.

Alexis Weissenberg, piano

Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Carlo Maria Giulini, conductor

Digitally remastered

Alexis Weissenberg

was born in Sofia, Bulgaria on 26 July 1929.

Biography1After receiving his first lessons from his mother, he started piano and composition studies at the age of five with the leading Bulgarian composer, Pancho Vladigerov. Weissenberg would later write of his mentor, He was an intuitive, flexible teacher, rather than a square pedagogue, and gave us, his pupils, an early awareness of temperament as a tool rather than a spice (*). At Vladigerov’s, he would listen to pianists such as Dinu Lipatti perform.

Weissenberg gave his first recital at the age of ten. It was my first physical connection with the stage, he wrote in “A Little Autobiographical Essay“. I loved it. I played three Bach Inventions, a few pieces from Schumann’s Album for the Young, Beethoven’s Capriccio for the Lost Penny, and an Improvisation by Vladigerov, and as an encore (I was so proud) an Etude of my own in G major, which I transcribed, at the last minute, in E flat major because´it sounded better’.

In 1943, two years after Bulgaria allied itself with the Axis Powers, he left the country with his mother. In spite of being held for three atrocious months in a detention camp at the border with Turkey, and after a short stay in Istanbul, they finally reached Palestine.

There, at the Jerusalem Academy of Music, he studied piano under Alfred Schröder (co-disciple of Artur Schnabel) and harmony and composition under Joseph Grünthal (Josef Tal). Very soon he had his first concert with orchestra (Beethoven’s Third with the Jerusalem Radio Orchestra). Just after the war’s end, Professor Leo Kestenberg, general manager of the Palestine Orchestra, offered him an engagement for three consecutive seasons, the last of which was conducted by Leonard Bernstein. He started a major tour in South Africa, consisting of 15 concerts with four different recital programs and five concerti.

Biography2Then, in 1946, he moved to the US, with two letters of recommendation from Kestenberg, one for Artur Schnabel, the other for Vladimir Horowitz. Weissenberg writes that he had one in each pocket, each one re-read 15 times. Both letters signed by Kestenberg. Both, separately, gave me the same advice. The inspiring teaching and influential musicianship and enthusiasm of Vladigerov, during the years in Sofia, had prepared me pianistically in the best pedagogical tradition. What I needed urgently was broader knowledge, much more cultural information, also maybe the experience of a school as opposed to private lessons, one or two competitions (why not?) in addition to patience and listening to as much music as possible (*).

He received lessons from Artur Schnabel and Wanda Landowska and was accepted to The Juilliard School of Music, where he enrolled in the studio of Olga Samaroff, who together with Rosina Lhévinne, shared the top talents of the times.

He also enrolled in the Composition and Musical Analysis classes of Vincent Persichetti, himself an excellent composer, who, in Weissenberg’s own words, considered eccentric ideas and original thinking a must (*).

In 1947, he won both the Leventritt Competition and the Philadelphia Youth Competition.

With these awards, his career flourished and that same year, he made his US debut performing Chopin’s Piano Concerto no.1 with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under George Szell and Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto no.3 with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugène Ormandy.

In 1956, he moved to Paris, where for some years he basically stayed away from the major stages, working on his technique and repertoire. He wrote this time: As a young artist, I learned new works very fast and played them much too soon. In 10 years, I would have reached a point where my whole repertory would have been overplayed and understudied. I did not want to end up at the age of 50 still a´promising pianist´ (*).

In the mid-1960’s, he re-launched his career, playing throughout Europe, the United States, South America and Japan, at the most important venues and with the greatest orchestras; under the most famous batons such as Szell, Ormandy, Steinberg, Maazel, Giulini, Abbado, Karajan, Celibidache or Ozawa. He was also completely in his element accompanying singers like Teresa Berganza, Plácido Domingo, Montserrat Caballé, Ferruccio Furlanetto or Hermann Prey.

Since then I have had the same experiences as my colleagues: many anxieties and rewards of learning the profession; doubts and joys due to the inevitable tension between the instinctive impulse and the technique of the performance; the enormous individual responsibility resulting from technical skill and creative expression; the monotonous life between suitcases and concert halls; but also, and above all, moments of sheer delight when the communication, that magic interaction between audience and artist, between musical director and soloist, between two sensitive souls, takes place.

It is a life where the choices one makes reflect the powerful desire to improve, to perfect, to simplify, to revise, relearn and re-state. These are my greatest motivations and they are also the main source of my almost infinite hope (*)!

This album contains no booklet.